Countless pieces of cider writing start by documenting the long and rich cider history of the 18th and 19th centuries in America. Modern day cider drinks love to revel in the mysticism of the the glorious cider culture of the past: Cider was consumed by the barrel; John Adams drank two tankards a day; The lore of Johnny Appleseed. All of this heritage and tradition has been fuel for the modern cider movement used in its marketing and message.

There is no shortage of 19th century texts about fruit growing, and even a few about making cider. But there aren’t many resources talking about what people actually drank. That’s why it’s so exciting that The New York Public Library has assembled and cataloged an impressive amount of restaurant menus from the mid-1800s to today. This collection gives insight into what drinkers have been consuming on a regular basis for almost 200 years. The brands, language, position and price all give insight into people’s relationship with cider and cider’s relationship to other beverages.

Cider, in some form, appears on menus throughout the final years of the 19th century and up to Prohibition. The standout difference, comparing many of these menu to the restaurants of today, is the vast diversity of items. It was not uncommon for simple restaurants to serve over 100 different dishes. Beverage lists mirror the complexities with deep cellars at even more casual establishments. Cider did not play a large role on any of the menus, but you can definitely find it on historic menus from across the country.

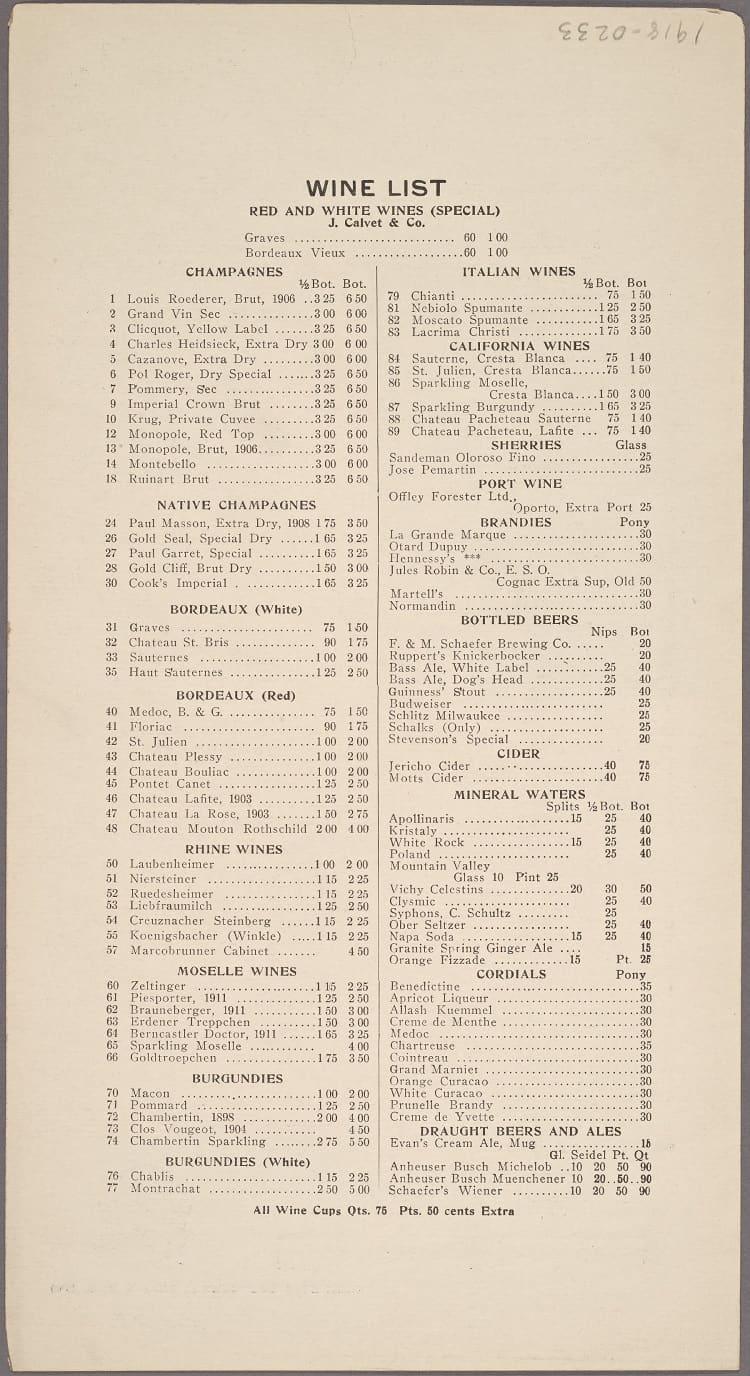

The ongoing debate for the place of cider on menus is not new to our generation. Cider appears under countless different headings and categorization throughout the Library’s collection. In 1900, Dorlon’s Oyster House, formerly located at 6 East 24rd Street in Manhattan, ciders were listed under the “Ale, Beer, etc.” category. While in 1918, cider was given its own category at Healy’s Forty-Second Street Restaurant, though the restaurant only boasted two offerings.

Healy’s Forty-Second Street Restaurant

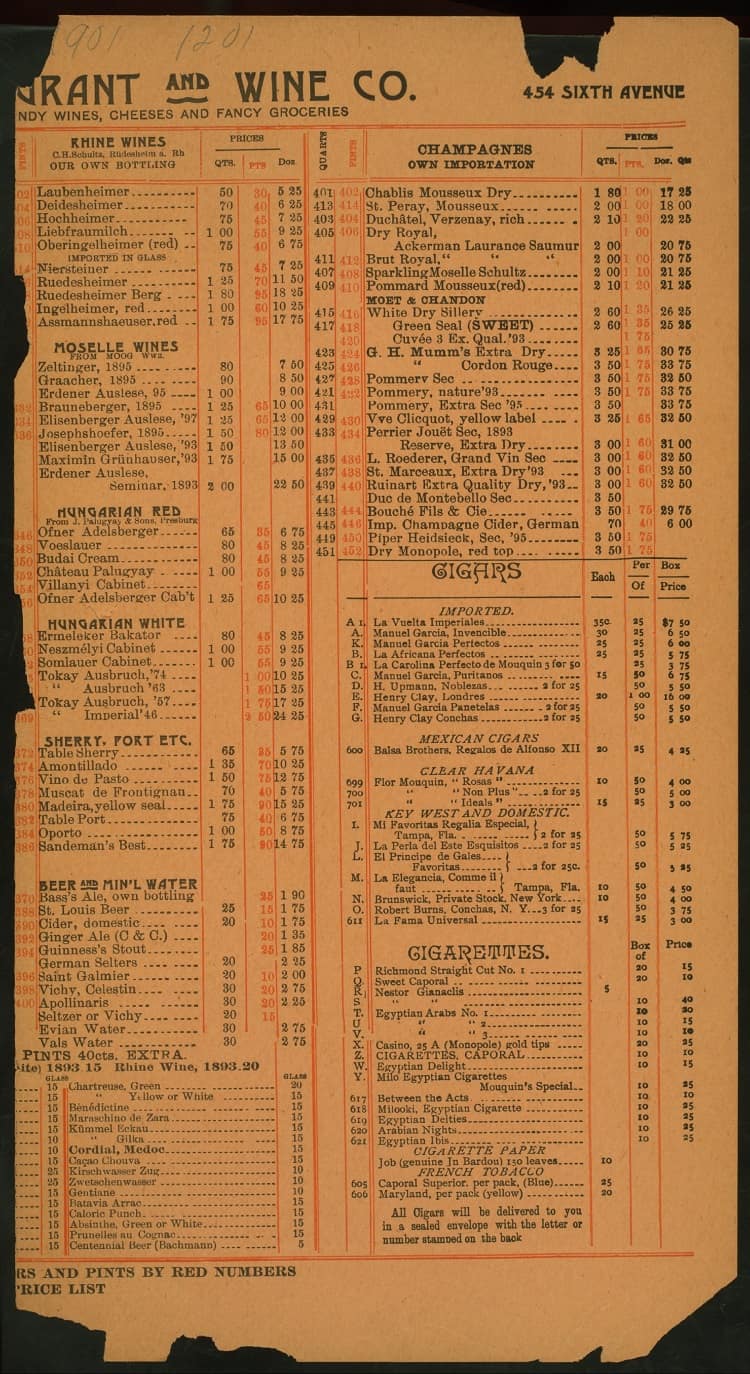

At many other places cider is grouped under a miscellaneous category that might encompass ginger ale, mineral water and lemonade, like at the posh Cafe St. Denis in midtown Manhattan, or the Kensington Hotel, both from 1901. Uniquely, Mouquin Restaurant and Wine Store on the Upper West Side listed cider in two places on its wine card: First, it appears under the “Beer and Mineral Water” category (for twenty cents a quart), while elsewhere on the menu “Imp. Champagne Cider” is listed for 70 cents under “Imported Champagne.”

Mouquin Restaurant and Wine Store

Another confusing point on the menus is the term “cider.” Within the cider community it’s long been believed that the term changed from meaning alcoholic cider to sweet unfermented juice as a result of Prohibition. The menus in this collection challenge that assumption. Menus from 1905 at the Harvard Faculty Club and the Hotel Metropole in St. Joseph, Missouri both list cider alongside strictly non-alcoholic beverages. This suggests that these ciders were non-alcoholic. Duff’s Golden Russet Cider may have been a sterilized non-alcoholic cider, but often appears with other alcoholic brands. Temperance establishments thrived throughout the 19th century, and this suggests that the vocabulary shift may have begun decades before Prohibition.

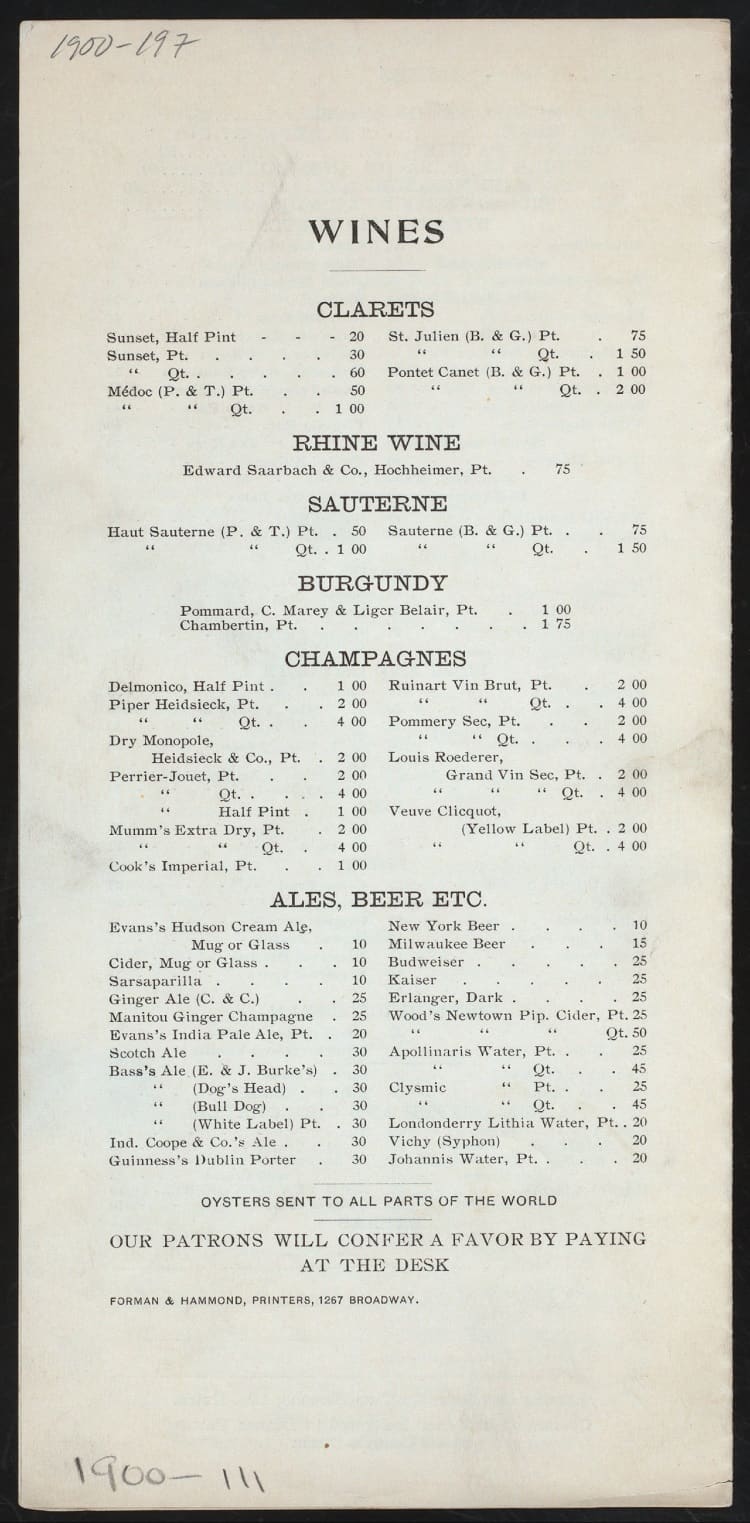

Generally, at most establishments, the cider selections are limited to a single cider, but a handful had multiple offerings. Dorlon’s Oyster House featured a generic cider by the mug or glass, as well as pints and quarts of Wood’s Newtown Pippin Cider. At 10 cents, the unbranded cider cost the same as local New York beers, while at 25 cents, Wood’s Newtown Pippin cider costs the same as Budweiser shipped in from St. Louis or Manitou Ginger Champagne from Colorado.

Dorlon’s Oyster House

Cafe St. Denis in 1901 listed several ciders: Sweet Cider, Cider Cup, Hick’s Russet (sparkling) and John F. Wood Co. Champagne Cider, making it one of the largest in the collection. At 80 cents a quart, the Champagne Cider is priced closer to domestic American wines but above several of the red Bordeauxs. The Gould’s Hotel in Boston in 1900 listed two ciders: S.S. Pierce and Gerry, both at 10 cents for a half pint and 20 cents for a full pint. It is priced closer between domestic beers (15 cents) and imported (25 cents). It appears that cider’s pricing a century ago was just as all over the place as it is today.

Pauldings Newtown Pippin Cider was made in Jericho, Long Island, New York and supposedly shipped around the world. On the wine menu of the USMS St. Louis, an Atlantic ocean liner making trips to Europe, one could buy a pint of Volnay or Rüdesheimer for nearly the same price as a quart of Pauldings. It was certainly one of the most common ciders in 19th-century New York. Rear Admiral Hiriam Pauldings, a career naval officer who served in both the War of 1812 and the Civil War, purchased the orchard in 1837 and it was run by his descendants until after the second World War.

Specificity in apples is a consistent theme throughout the menus, not just in cider but as fruit. For decades, The Waldorf Astoria in New York had the option of Newtown Pippin or Esopus Spitzenburg on its dessert menu. Chateau Frontenac in Quebec and the Palliser Hotel in Calgary in 1937 both list local Canadian apples on their menu as a point of pride.

These century-old menus from some of the finest establishments of the time offer a window into the cider culture of a century ago. Cider had a place among the library of selections offered by restaurants, and while it held a consistent market in cities, cider was eclipsed more generally by wine and beer (sounds much like today, huh?). After Prohibition was repealed in 1933, wine and beer culture were able to slowly rebuild themselves, while cider withdrew from the cities and returned to its rural roots.

While it is difficult, and perhaps unwise, to draw direct parallels to today’s craft cider market, it is fascinating to observe the similarities and differences. Most importantly, we get to see how our market will grow and evolve without a 13-year period of Prohibition to stand in our way.