This essay originally appeared in Issue 13 (2021) of the zine Malus.

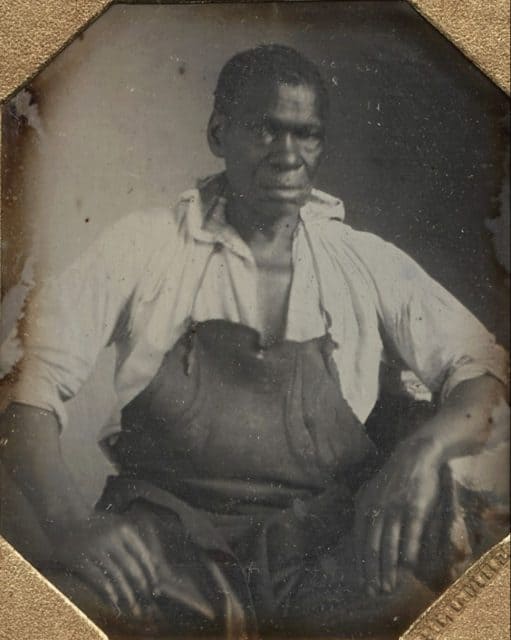

Isaac Granger Jefferson ca. 1845, blacksmith at Monticello and son of George and Ursula Granger. There are no images of his enslaved parents, who were both involved with cidermaking there.

Historical research can be a frustrating business. Documentary records tend to be maddeningly incomplete. What might be key documents are often absent — tossed out by a well-meaning clerk, destroyed by water or rodents, or simply left to molder away in some forgotten corner. Unremarkable farm work, like cidermaking, was often left uncommented upon anyway, and was typically done by ordinary people — working people, farmers and hired hands, skilled perhaps, but often illiterate, and certainly not part of the venerated class of Great Men who get scholarly biographies. Documents containing information about the lives and work of enslaved Africans and their descendants are even sparser.

This is the challenge of writing about Black cidermaking in America. But one can hardly hope to understand the history of American cider without considering African participation in it. So far, the cider community as a whole has done a pretty poor job of ferreting out this history, especially when it comes to narratives involving the enslaved. There has been a fixation on Jupiter Evans, an enslaved man at Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia plantation, Monticello, while other Black people involved in early American cidermaking have been largely ignored. There is much to be learned for those with the courage to dig beyond the half-dozen websites that pop up with a simple internet search. This essay just scratches the surface.

Patriots, Puritans, and White Gold

We start here with New England. We don’t think much about the existence of slavery in New England, but the farms and plantations there were major suppliers of essential goods to the West Indies, where resources were more profitably spent on producing sugar, often referred to as white gold. With continual labor shortages, landowners made used of enslaved Africans, though in fewer numbers than in the Southern colonies as the labor required to produce subsistence goods was less than that for tobacco or cotton. New England producers provided the sugar colonies with meat, lumber, and wheat as well as apples and cider.

As with so much of early American history, definitive documentary evidence showing that slave labor was used to produce cider in New England is scant, but much can be inferred from the available records. By carefully examining probate records in eastern Rhode Island between 1638 and 1800, for example, one historian concluded that planters that owned slaves were much more likely to produce cider for sale than their non-slave owning neighbors (Garmen, 1998) and that cidermaking took more skill than, say, field work. Two particular examples of this practice can be found in the records of Sylvester Manor in New York and Ten Hills Farm in Massachusetts.

Sylvester Manor was built by Nathaniel Sylvester (1610-1680) on Shelter Island at the eastern end of Long Island, land purchased from the Manhasset, many of whom remained living there. His intention was to provision the Barbados sugar plantation he owned in partnership with his brother and two others, and the inventory made at his death shows that he owned a cider mill, as well as a number of Africans, including Tammero, Oyou, Black John, J:O, Maria, Jenkin, Tony, Nannie, Japhet, Semenie, Jaquero, and Hannah, plus their children. Nathaniel Sylvester left neither accounts nor a diary, so we cannot know for certain who of these might have made cider. Considering the amount and scope of work on the plantation, and just how few people there were to do it, it would not be unreasonable to imagine that almost everyone contributed at one time or another. The account books left by Nathaniel’s eldest son and heir, Giles (1657-1708), support this notion, for they show that outside help was needed on the plantation during the fall, the busiest time of the year. He hired a number of local Manhasset men to augment the work done by his enslaved laborers, including one named Henry who was paid for 55 days of cidermaking one year. Cider was used to pay for labor, in trade for corn, and was also sold locally to neighbors, nearby Native Americans, and, in one entry, to Black John.

18th Century cider mill along the Schuylkill River, PA

Provisioning sugar plantations was also the business of Ten Hills Farm, owned by Isaac Royall, Sr. (1677-1739) from 1732. A New England native, he made his initial fortune in trading slaves, sugar, and rum from his Antigua plantation. After a slave revolt there in 1737 (Royall’s enslaved driver Hector was executed for his role in the uprising), Royall and his family returned to Massachusetts where he had been building a stylish house with outbuildings and orchards on 500 acres abutting the Mystic River in Middlesex County near Boston. Documents show that he brought slaves with him (he petitioned the general court to avoid paying import taxes on them because they were “for his own use, and not to sell them”), and these he divided among his heirs upon his death in 1739, including his only son, Isaac Royall, Jr. (1719-1781) who carried on the family business.

Royall, Jr. also does not appear to have left a diary, but his cidermaking activity can be seen in his tax records. Along with wool, grain, and livestock, tax records from 1771 show the production of 26 barrels of cider and five “servants for life,” as they were so delicately referred to, though with no names. They may have been Betsey, George, Hagar, Myra, Nancy, or Stephen, who were all still at Ten Hills Farm in 1776 when Royall directed they be sold (he fled to England at the start of the Revolutionary War and needed the money). There were at least 254 enslaved persons in Middlesex County that year and 34,164 barrels of cider made, more than any other county in Massachusetts. Can we be absolutely certain that the Royall’s cider was made by enslaved people? Not with the current records, though given the Royalls’ history in Antigua it is hard to imagine otherwise. Isaac Royall, Jr.’s bequest to Harvard College, incidentally, was a key factor in the founding of its law school.

Business as Usual

We know a little more about cidermaking at Ferry Hill, a 700 acre plantation owned by John Blackford (1771-1839) on the Potomac River outside Sharpsburg, MD. It was a mixed agricultural operation whose main commercial crop was wheat, though Blackford also sold wood in various forms and a number of apple products, including cider. He used a combination of slave labor and hired whites and free Blacks, owning roughly 25 people at his death according to probate records. He seems to have been intimately involved in running his farm, and kept a good diary (the one for 1838-1839 is available digitally). He also seems to have had trouble with his cider mill, for he hired someone to work on it several times throughout the fall of 1838.

Blackford recorded the days his slaves gathered apples (Daphne, Caroline, and Isaiah) and worked with a hired hand to grind and press them. Others (Will, Enoch, and Julius) also pressed cider from pomace to make water cider (ciderkin) and vinegar. His son Franklin and a tenant pressed cider, too. Everyone seems to have been working alongside everyone else, which sounds almost egalitarian, and it seems that he gave many of his enslaved workers plenty of autonomy. The ads he placed seeking the capture of several that ran away, and his readiness to return the fleeing slaves of others he found hiding near the Potomac, make clear that his “people” weren’t people, though. They were property.

Early American Patriarchs

The two men that we probably think we know the most about when it comes to early American cidermaking involving enslaved people are George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. They both fall into the category of Great Men, therefore much effort has been put into preserving, analyzing, and digitizing their written legacies. Even so, we are still confronted with the ordinariness of cidermaking, and the smallness of the people doing the actual work.

Washington’s 8,000 or so acre plantation at Mt. Vernon on the Potomac River in eastern Virginia consisted of a number of different contiguous farms: River Farm, Dogue Run, Muddy Hole, Union Farm, and Mansion House. Each farm had its own set of buildings and purpose — one had a mill, another a distillery — and its own separate set of workers, most of whom where enslaved. There also were hired laborers and an overseer, who reported to a single farm manager that was responsible for the whole plantation. We know many of the names of the enslaved, thanks to the annual tithe (tax) reports required by the Virginia colony as well as two inventories written by Washington in 1786 and 1799, when there were 251 enslaved persons at Mt. Vernon, though we know little more than that. A number of Washington’s “people” were trained in skilled trades like carpentry, cooperage, or smithing, and a few worked as overseers. This is an important point, for several written contracts between Washington and his various white overseers clearly show that it was the overseer that had responsibility for annual cidermaking, and that this was probably the norm. “By the Bearer you will receive a Gross of (Hues) Crabb Cyder, wch[sic] you will much oblige me by accepting,” wrote Washington’s nephew William Augustine Washington in 1785, “‘Tho not so good as I could wish, from the management of my Cyder last fall being left intirely[sic] to the Negroes, from the Loss of both my Overseers.”

Who were Washington’s Black overseers then? Will oversaw several farms including Muddy Hole (1785) and Dogue Run (1792). Israel Morris oversaw Dogue Run from 1766 until 1794. He was gone by the making of the 1799 inventory, and had probably died. Davy Gray ran Muddy Hole from 1770 until 1785, then River Farm for a few years, moving back to Muddy Hole in 1792 and remaining there until Washington’s death in 1799. Cider was made at many, possibly all, of the farms. “My Ox Cart finished drawing in the Wheat at Doeg Run–but during this time it was employed in getting home the Cyder from all the Plantations,” Washington wrote in his diary in September 1768. ”In the Neck [River Farm]…The other hands except those at the Plow and employed in getting in and Stacking the Wheat—were threshing out Oats, & pressing Cyder,” reads an entry in August 1788.

Davy Gray was born in 1743 (deducible from the 1799 inventory), and was married to Molly (born 1723). It is possible that he trained as a gardener; that was Washington’s stated intent in a 1762 letter, at least. Gray, Molly, Will, and Morris were among the 80 dower slaves that came to Washington upon his marriage to the widow Martha Custis. As such they, and their children, could not be freed or sold; those still living were inherited by the heirs of her first husband upon Martha Washington’s death in 1802. Davy Gray’s appearance in the probate inventory is the only reason we know his last name as it appears nowhere else in Washington’s records.

Monticello

Jefferson’s records are possibly more complete than Washington’s, for he not only kept accounts but also a farm book and a garden book where he recorded much of what went on at his Monticello plantation, at least sporadically. Both planting/grafting trees and cidermaking show up in his correspondence as well. It is fortunate that Jefferson has held such a fascination for so many for almost everything that remains of his writings has been digitized and is freely available to the public.

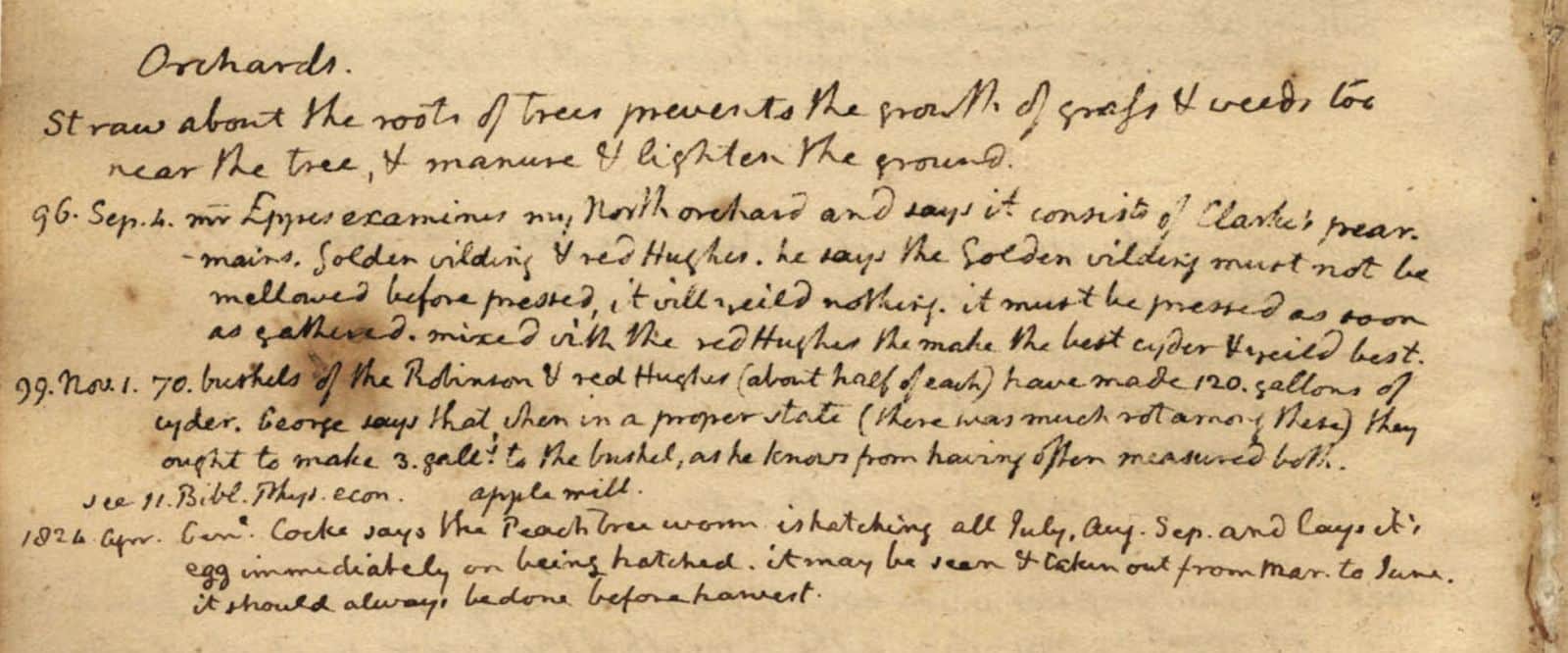

Which brings us to George Granger, or Great George as Jefferson called him. Jefferson bought George Granger (1730-1799) from Wade Netherland in, probably, 1773 near the time when he bought Granger’s wife Ursula (1738-1800) and their children from the estate of John Fleming. Martha Jefferson apparently admired Ursula Granger’s cooking. Some time before 1787, George Granger became responsible for Jefferson’s orchards. “. . . George still to be reserved to take care of my orchards,” he wrote to his overseer that July, and by 1790 was the overseer of Monticello, the only Black overseer to work there. He is said to have been literate, something that was not the case for all of Jefferson’s white overseers. He very clearly also made cider. Jefferson’s entry for 1 November 1799 reads “70 bushels of the Robinson & red Hughes . . . have made 120 gallons of cyder. George says that when in a proper state (there was much rot among these) they ought to make 3 galls. to the bushel, as he knows from having often measured both (emphasis added).” To have that kind of knowledge, Granger is likely to have been making cider for some time.

The entry in Jefferson’s Farm Book documenting George Granger pressing apples for cider; Granger died the next day.

Ursula Granger also had a hand in the cidermaking process. “I must get Martha [Jefferson’s daughter] or yourself to give orders for bottling the cyder in the proper season in March,” Jefferson wrote to his son-in-law on 4 February 1800. “There is nobody there but Ursula who unites trust & skill to do it. She may take any body she pleases to aid her.” Ursula was a pastry cook, from what little we know of her, though she also supervised the salting of meat to preserve it, washed and ironed the Jeffersons’ clothes, and sometimes acted as wet nurse to the Jefferson children. Both she and her husband, as well as their son George, Jr., died within six months of each other in 1799-1800.

Jefferson’s records don’t have much to say about cidermaking after 1800, with the exception of an instruction to Edmund Bacon (1785-1866), overseer at Monticello from 1806 to 1822. “We have saved red Hughes enough from the North orchard to make a smart cask of cyder,” Jefferson wrote to Bacon in November 1817. “[T]hey are now mellow & beginning to rot. I will pray you therefore to have them made into cyder immediately. let them be made clean one by one, and all the rotten ones thrown away or the rot cut out. nothing else can ensure fine cyder,” again suggesting that managing cidermaking was part of an overseer’s job.

It is from Bacon that we get one more hint about the role the enslaved at Monticello played in making cider there. Late in life he sat down with one Hamilton Pierson and reminisced about working for Jefferson. In Pierson’s book recounting their conversations, Bacon speaks of some of the house servants: Betty Brown, Sally, Critta, and Betty Hemings, Nance, and Ursula (not Granger, who had died many years before). “These women remained at Monticello while he was President,” he said. “I was instructed to take no control of them. They had very little to do. When I opened the house, they attended to airing it. Then every March we had to bottle all his cider. Dear me, this was a job. It took us two weeks. Mr. Jefferson was very particular about his cider.”

Jupiter Evans: the Documentary Record

What then of Jupiter Evans? To be frank, there is little in the primary documents — the farm and garden books, memorandum book, or correspondence — that connects Evans to cidermaking. On 11 February 1800, Jefferson wrote a letter to his daughter. “The death of Jupiter obliges me to ask of Mr. Randolph or yourself to give orders at the proper time in March for the bottling [of] my cyder,” it said. He had also mentioned Evans in his letter of the previous week, “I am sorry for him [Evans] as well as sensible he leaves a void in my domestic administration which I cannot fill up—,” it says, followed by the sentence about Ursula and bottling cider (the mark between the two sentences appears in the original). Letters at this time weren’t typically divided into distinct paragraphs, appearing as one continuous flow even when subjects changed and the author moved on to the next item. Knowing that, and in light of the obvious mark dividing the two sentences, are they unambiguously part of the same thought? In the absence of any other documentary evidence, can these two statements alone be read to mean that Evans was Jefferson’s cidermaker?

Jefferson had known Evans his whole life. They grew up together, born on the same plantation in the same year. Evans spent 10 years as Jefferson’s personal attendant, replaced by the young Robert Hemings, then was put in charge of the stables, seeing to the wagons and carriages and Jefferson’s precious blooded horses. He was trained as a stonemason, working on a range of projects at both Monticello and hired out to others, especially when Jefferson was away for an extended period. They traveled together often, and records show that Evans was sometimes sent out alone with important documents or large sums of money. Jefferson clearly trusted him, and Evans probably had, from long experience, a good sense of how his master liked the household run. The fact that Jefferson sent instructions that either Martha or her husband, who were not cidermakers, were to step into Evans’ place and order the bottling suggests that Jefferson simply trusted him to see that this part of his domestic affairs ran smoothly. Perhaps as overseer, it would have been George Granger directing the bottling if he had not died the previous November.

Most of what we know about Evans and the Grangers comes from work done by Lucia Stanton, Senior Historian at the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, now retired. In the early 1990s she began conducting detailed research into the lives of the enslaved population at Monticello, work that transformed how the enslaved were presented both on site at the plantation, during tours there, and on the historic site’s website. It is interesting to note that Stanton’s published work includes aspects of cidermaking when she writes about the Grangers, but not when writing about Jupiter Evans.

In truth, though, whether or not Jupiter Evans was involved with cider at Monticello is not really the point. What is the point is that others clearly were, and that while the cider community lauds Jupiter Evans, the Grangers remain invisible. Tens of thousands of enslaved people lived, worked, and died in service of their owners, some making cider that would enrich those owners either in the marketplace or on their tables. To avoid spending time and effort to learn more of their lives, even if it is just their names, does a grave disservice to their memory, and perpetuates the dismissal of Black and indigenous people’s part in America’s cider history. Black John, Henry, Daphne, Israel Morris, Davy Gray, George and Ursula Granger all deserve better.

Resources and Suggested Reading:

- Chan, Alexandra A., “The Slaves of Colonial New England: Discourses of Colonialism and Identity at the Isaac Royall House, Medford, Massachusetts, 1732-1773, Vol. I of II” PhD diss., Boston University, 2007

- Garman, James, C., “Rethinking “Resistant Accommodation”: Toward an Archaeology of African-American Lives in Southern New England, 1638-1800”, Int. J. of Historical Archaeology, Vol. 2, No. 2 (1998): 133-160

- Grivno, Max L., “Historic Resource Study: Ferry Hill Plantation” (National Park Service, 2007)

- Pierson, Hamilton W., “The Private Life of Thomas Jefferson from Entirely New Materials” (New York, Charles Scribner, 1862), 106-107

- Priddy, Katherine Lee, “From Youghco to Black John: Ethnohistory of Sylvester Manor, ca. 1600-1735”, Northeast Historical Archaeology, Vol. 36 The Historical Archaeology of Sylvester Manor, Article 4 (2007): 16-33

- Stanton, Lucia, “Those Who Labor for My Happiness”(University of Virginia Press, 2012)

- Thompson, Mary V., “The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret” (University of Virginia Press, 2019)

- Trigg, Heather, and David B. Landon, “Labor and Agricultural Production at Sylvester Manor Plantation, Shelter Island, New York”, Historical Archaeology, Vol. 44, No. 3 (2010): 36-53

- Trigg, Heather and Ashley Leasure, “Cider, Wheat, Maize, and Firewood: Paleoethnobotany at Sylvester Manor”, Northeast Historical Archaeology, Vol. 36 The Historical Archaeology of Sylvester Manor, Article 10 (2007): 113-126

- Documenting the American South

- Founders Online at the National Archives

- Medford Historical Society Papers at the Perseus Digital Library at Tufts University

- Monticello

- George Washington’s Mount Vernon

- Royall House and Slave Quarters

- 1771 Massachusetts Tax Inventory

- Sylvester Manor

Thank you to Angry Orchard Hard Cider for sponsoring the re-print of this post on Cider Culture.

- Photos and images: Courtesy of Darlene Hayes