Do you dream of making cider commercially, with visions of a cool taproom you design from scratch dancing in your head? That may not be feasible right away considering the high startup costs that come with opening a brick-and-mortar location. So, what’s a budding cider maker to do? Many cider startups begin with contracting the production process.

To explain the ups and downs of this path to commercial production, we spoke with three cider makers who got their start without their own production facilities. Instead, they partnered with existing cideries, wineries or breweries to bring their cider recipes to fruition.

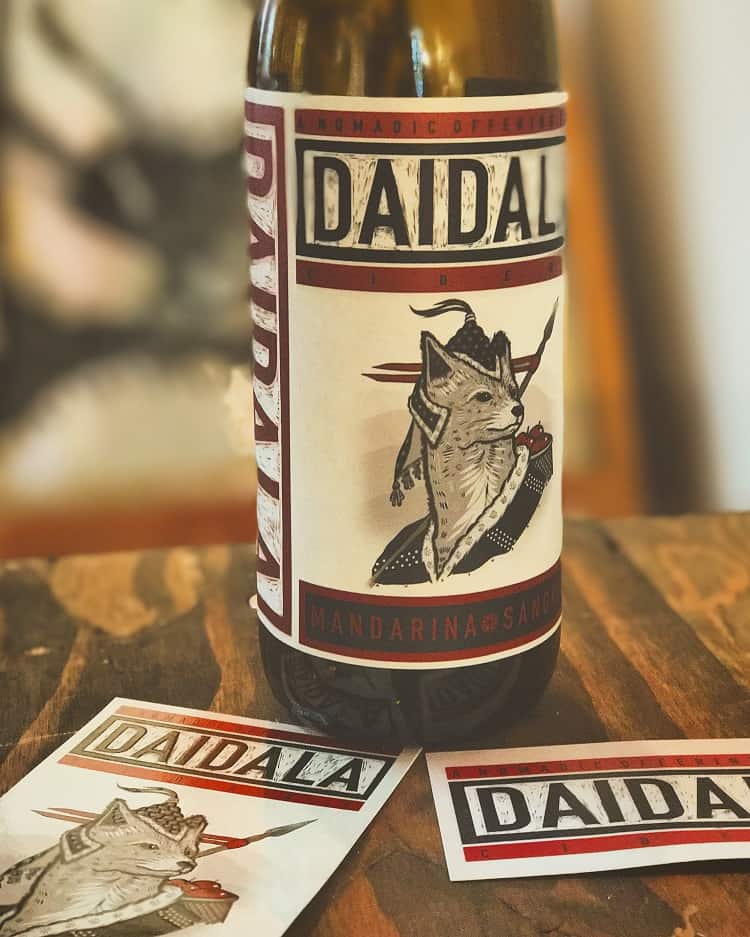

Daidala Ciders

At just six months old, Daidala Ciders owner Chris Heagney feels good about his decision to start and continue brewing as what he calls a “nomadic cidery.” Inspired by gypsy craft breweries like Mikkeller, Evil Twin and Stillwater Artisanal Ales, Heagney says, “Not only did these brewers place a level of experimentation high on their priorities, but also valued the artwork that was associated with their brands. I found all of that very relatable.”

Currently Heagney’s ciders are only available at local restaurants and shops in his headquarters of Asheville and Charlotte, home to one of his contract cideries, Red Clay Ciderworks. Heagney approached Red Clay because its process and equipment fit the styles of cider he wanted to produce. But, he acknowledges that not having a place of his own creates “a slight void between us and our customers.”

Heagney has plans to change that “void” in 2018 by opening a hard cider shop in Asheville, but he currently doesn’t have plans to produce his own ciders there. “I have more freedom to experiment with small batch ciders. A typical producer might not bottle as many of their one-off ciders,” he explains. However, the low start-up costs were the ultimate factor in Heagney’s decision to start as a nomadic cidery.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BXbYd1pHhj_/?taken-by=daidalaciders

Other plans for 2018 include producing more draft: “Cider on tap is more popular than I was expecting — my original plan was to limit the number of kegs produced while packaging more in bottles. I regret not allocating funds from the start to buy my own stainless steel kegs, rather than using recyclable kegs,” Heagney says. But as he’s done throughout his first year in business, he will continue to pivot and tweak his business as the cider industry continues to grow.

He adds, “Every day, more people are realizing that cider is not just a syrupy, soda-esque beverage, but a drink that can be as complex as wine or as adventurous as craft beer. There are still many parts of the country that don’t have any local cideries, and the cider selection on the shelves can be frustratingly thin. I believe that over the next five years, more and more cideries will open their doors with success.”

Kurant Cider

After three years of contract brewing, renovations are underway at Kurant Cider’s future home in the Fishtown neighborhood of Philadelphia. “Our five-year plan was to make wholesale work and fund the opening of our own taproom/cidery around year three. We’re mostly on track with our original plan still. It’s pretty amazing,” says Joe Getz, owner of Kurant Cider.

Kurant Cider’s future home in Philadelphia

Yet, the journey has come with plenty of challenges, mainly centered on working around somebody else’s schedule. “We write our production plan up to a year in advance so everybody is on the same page. If we sell out of a cider, sometimes it can be several weeks before we can restock. We’re constantly guessing at sales projections to line up production, and if we’re wrong, there are consequences,” he explains.

Kurant is currently working with its second contract brewery after outgrowing the space available at Round Guys Brewing Co., its first contracted facility. “They let us stick tanks in their brewhouse and let us borrow things here and there when we needed them. They were extremely helpful,” he says. Now, Kurant is working with Free Will Brewing Co., but Getz is quick to urge others who are thinking about the contract path to do their homework. “If you don’t have the capital to open a taproom and small production facility, don’t try to go pro. The real money to be made is in retail pouring cider out of your own taps.”

Kurant owner, Joe Getz, on the left

Getz notes that the wholesale game is extremely competitive, and it’s only getting harder as cider’s popularity expands. “We made it work, but the market has changed since just a few years ago when we launched. If you’re not pumping out thousands of gallons at a time either in cans or bottles for store shelves with a solid distribution network, you’ll go broke trying to survive on just wholesale.”

While that may sound like Getz regrets Kurant’s path, he acknowledges the attractiveness of starting up a cidery at about 20% of what it would cost to open your own space. “I don’t like to look backwards. We’ve certainly learned from mistakes along the way,” he says. “Building a taproom and production facility is extremely expensive. We just didn’t have the capital to do it when we started.”

Like Heagney, Getz sees the growth potential in the U.S. cider market and believes the biggest hurdle is consumer education. “Consumers are typically unaware what cider can be as a product, and how diverse cider offerings are. They think it’s all the same. I hope in five years people will be able to say they like sidra natural, but they don’t like hopped cider. We’re working hard to educate people.”

Original 13 Ciderworks

Another Philadelphia cidery, Original 13 Ciderworks, also launched as a contract brewery “simply to see if we even had it to brew a commercially successful product.” Founder John Kowchak says, “I was happy when I was selling three or four kegs a month.”

Now, five years later, Original 13 is a 5,000-gallon capacity cidery with distribution in two states. But, in the beginning, Kowchak could only find one winery that was willing to contract brew for him. “We approached dozens of wineries, but they either wanted to charge exuberant rates or had no available tank space,” he says.

Recent changes in Pennsylvania law that allows wineries and cideries to sell directly to the public caused Kowchak to do “a complete 180 on our initial plan to have a simple tasting room and cidery. We revamped our plan into a full bar and restaurant.”

Kowchak moved away from contract brewing as quickly as possible because he didn’t like the lack of control over his product. He says contract brewing led to issues with the quality and stability of his ciders and initially damaged their reputation and brand. “If you just want to get into the game of selling a product commercially to test the viability of it, then starting with a contractor might be a more cost-effective solution. Just make sure you trust your contractor, that they are willing to listen to you, and that you have all the legal contracts in place to protect yourself and your brand. If you have any reason not to trust them, then don’t get involved with them,” he advises.

Taking the time to grow has been vital to Original 13’s success in the business, Kowchak says, and he truly has no regrets about starting out as a contract cidery. “Even our failures and times of struggle gave us insight into how to do things better,” he notes. Now, with complete control over its operations, Original 13 Ciderworks is growing into a regional brand with a couple of taprooms. “In the end, for me at least, it’s about creating good paying jobs. I would like to be making enough to make sure my employees are well taken care of and we are able to bring even more people onboard.”

- Feature photo and Sir Charles Cider photo: Original 13 Ciderworks

- Kurant Cider photos: Kurant Cider

- Daidala Ciders photo: Daidala Ciders